Different Direction — Political Fashion of Today

With fashion's influence spanning continents and communities, it has the power to conjure society's aspirations and challenge established norms. Its intersections with political and social movements prove its function as a mirror of our times, used to express patriotic, nationalistic, and propagandistic tendencies. In the chaos of today’s political climate and the constant reminder that our current events will one day fill history books, it begs the question: what role does fashion play in this story? While the relationship between politics and fashion shifts with each era, the two are inseparable, constantly shaping and reflecting one another. To put it bluntly, the two have nothing and everything in common.

During the suffragette movement in the 1920s, fashion acted as a silent yet compelling communicator as women took great strides in the march toward equality. The signature colors of white, green, and purple stood as key symbols — white symbolized purity, purple represented dignity, and green signified hope. The suffragettes’ abandonment of restrictive clothing and instead opting for comfort was a rejection of traditionalism and rigid expectations. Challenging these norms sparked a dramatic shift in fashion, ultimately paving the way toward women’s independence. The comfort and functionality they championed in their methodical protest laid the groundwork for today’s emphasis on gender equality and body autonomy in fashion. To gain deeper insight into the significance of this movement, I spoke with Clare Sauro, lead curator of the Robert and Penny Fox Historic Costume Collection.

“Clothing is about community and self-expression at the same time,” notes Sauro. “There’s always this push-pull between fitting in, standing out, and making a statement in some capacity.” She goes on to point out the mindfulness that the suffragettes needed to exude if they wanted to be taken seriously. “They were very focused on being respectable. Even while they were protesting, they wanted to show that they were controlled, measured, and thoughtful.” The carefulness of the suffragettes showed the importance of tactical movements in a playground for fashion and rebellion. The suffragettes not only advanced women’s rights but demonstrated the power of fashion as a vehicle for revolution — a medium we’d see again in the coming years.

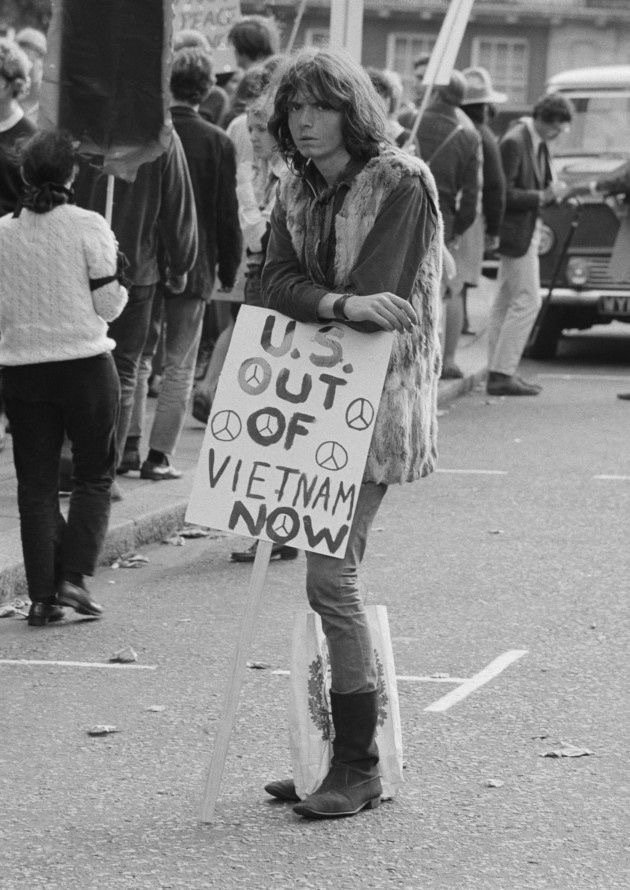

Once again, fashion took a sharp turn towards revolt in the 1960s, where the anti-war counterculture protesters challenged the norms set by older generations and rejected materialistic consumerism. Utilizing non-traditional, non-structured clothing — like bell-bottom jeans, tie-dyed fabrics, kaftans, and bright colors — the demonstrators symbolized a commitment to peace, love, and freedom, rejecting the US’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Designers popular during this period, including Mary Quant, marketed their clothing by billing it as a means for change, making their products transcend barriers. Famously associated with popularizing the mini skirt, Quant firmly believed that “Good taste is death. Vulgarity is life,” with her work reflecting a rejection of the conservative and formal styles of the previous generation. History repeats itself on today’s runways, where revitalized bohemian and strikingly rebellious aesthetics appear with flowing maxi dresses, ethnic prints, and natural fabrics. The legacy left by the counterculture reminds us that fashion is an undeniable force for change and connection.

Political fashion today ventures outside the typical boundaries of a thirst for change — it is now a statement of identity, ultimately shaping the collective. Recently, college campuses have been used as canvases for expressive freedom and runways where individuals celebrate gender fluidity — and that, in itself, is a political statement. Where the 60s counterculture demonstrators challenged societal norms with long, tangled hair and rock music, we break down our wardrobes and make individual garments inclusive for all. The loosened grip of gender binaries is exemplified by celebrity figures such as Harry Styles, who rocked a custom-made Gucci dress on the cover of American Vogue, and the late David Bowie, whose gender-bending legacy lives on through his alter-ego, Ziggy Stardust.

“Gender is constructed, just like politics is a construction,” says Dr. Joseph Hancock, Retail & Merchandising professor at Drexel University. “The way we make statements about who we are and express ourselves in this political agenda is through the power of garments.” He points out past red carpet moments of figures like Boy George, Annie Lennox, and disco singer Sylvester and how the shock value of non-conformity has diminished over the years. When asked about the progress of political implications and barrier-breaking, Hancock explained, “We’re very inquisitive as to why people wear what we do. That’s what makes us good people. We’re interested in asking and exposing ourselves to different people — and that’s what’s important.”

Closer to home, binary-breaking is not confined to the world of celebrities. Right here on campus, these shifts are embodied through the bold stylistic expression of individuals like Simone Bollinger, a Fashion Industry & Merchandising student whose androgynous style reflects a deliberate challenge of societal expectations. Their fashion not only blurs the line between masculine and feminine expectations of dress but serves as a powerful form of self-expression, aligning with historical movements that advocated for freedom, gender equality, and inclusivity. When describing their style, Bollinger shares, “Some days, I can go from feeling really feminine and wanting to wear super feminine clothing to feeling really masculine. Then, some days, I’m just not really feeling either. Let me do a little bit of everything,”

While Bollinger’s clothing choices reflect personal aesthetics and a rejection of gendered norms, they are firmly rooted in their advocacy for others to feel entirely comfortable in who they are. “The current political state of the world could have some negative influence on people feeling comfortable expressing themselves because they might feel more scared or nervous, which does make me very sad,” Bollinger explains, “But I do hope that [genderfluid fashion] is something that will continue to grow no matter how much people are afraid.”

For others who may be questioning their own gender identity and searching for an outlet, Simone says, “Go out and explore your style. Learn different things, be curious about things you don’t know a lot about. I feel like I would not be who I am today if I wasn’t curious and looked into a million different things.”

Whether we realize it or not, the outfits we pull together are political. Every time we step into stores and pull items from a section that’s not “ours” or mix patterns that don’t traditionally suit each other, we’re making a statement that rather than fitting neatly in a box, we’re designing our own. Looking back, the suffragettes used fashion as a battleground for women’s rights by wearing white sashes as a banner for justice. The hippies of the 60s used fringe and denim to reject traditionalist ideals. Today, when we question society’s gripping rules on fashion — whether it’s dismissing gendered clothing or simply owning our out-of-the-box choices — we echo the power of these movements. The yearning for justice, individuality, and freedom is heard in every footstep. The next time you visit your wardrobe, think of the garments you wear and remember that, yes, you’re making history too.